What's your favourite comic book movie? It's a question you may well be asking whilst in lockdown, and you may also be asking where the genre began on the big screen.

Here, then, is our exhaustive guide to the development of the comic book film, encompassing Marvel, DC and everything in-between.

If you're looking for movie inspiration, our feature could also double-up as a handy guide to all-time classics and hidden gems. Either way, the journey from inception to the present day is a rich and extensive one, as you're about to find out.

1. The genre is born:

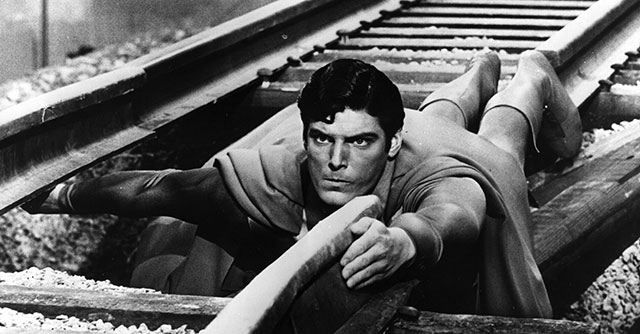

Superman (1978)

True, there had been other comic book/graphic novel movies prior to Superman's triumphant, soaring big-screen debut. The campy Adam West Batman movie (spun off from the TV series) is just one example. ("Some days, you just can't get rid of a bomb!")

But no comic book film had quite seized on the potential of special effects quite like Superman did; the tagline read 'You'll believe a man can fly' and, in stark contrast to the usual marketeering rhetoric, it was absolutely true.

The flying effects in Richard Donner's monster hit (augmented by a characteristically spectacular John Williams score) broke new ground in their green screen immersiveness. But Superman was the first comic book movie to realise that all the bells and whistles need to be balanced with a sense of soul.

The movie achieved that with the pitch-perfect casting of the late Christopher Reeve, by turns endearing as the bumbling Clark Kent, and assured as the mighty Superman. Yet Reeve subtly exposes the fallacies behind Supes' logo and cape, whether it's his exposure to Kryptonite at the hands of the evil Lex Luthor (a scene-stealing Gene Hackman), or his anguish at the climactic death of Lois Lane (Margot Kidder), whose fate Supes promptly reverses.

So iconic is the movie that on-set stories have become the stuff of legend. One of the most famous is that actor Marlon Brando, playing Superman's father Jor-el, had to have his lines written on the baby's nappy during the opening Kryptonite sequences. Then there was the small matter of Brando's fee: an astronomical (for the time) $3.7 million for less than 20 minutes of screentime.

With its mixture of utterly believable effects, memorable score, star-making central performance and array of entertaining supporting players, Superman is arguably the grandfather of the comic book genre. It won a Special Achievement Oscar for its effects, was nominated for three more, and emerged as the highest-grossing film of the year with more than $300 million in the bank against a budget of $55 million.

2. The comic book movie becomes a blockbuster:

Batman (1989)

If Superman is the twinkly-eyed, optimistic grandfather of the comic book movie genre, then Tim Burton's Batman is the anguished, gothically-attired grandson. Far from being an upstart, Burton's movie broke through to a new generation of movie fans, including those apathetic to comic books, by virtue of its sheer style and design.

Superman may have been a box office success but Batman was a monster, the first summer movie release replete with merchandising deals and tie-in offers. That partially accounts for the film's world-shattering box office success – more than $411 million worldwide to be precise. Of course, another reason is that this was the first time Batman had been treated with any kind of sincerity and seriousness on the big screen.

Long before Christopher Nolan cleaned out the cobwebs of Joel Schumacher's Batman and Robin, Burton's movie had to tussle with the enduring legacy of Adam West's campy Batman portrayal from the 1960s. It was an image prevalent in the minds of moviegoers and comic book fans, but the film worked like a charm, for a number of reasons.

There was the quiet menace of Michael Keaton as the Dark Knight, a hugely controversial choice given he was best known for comedies, including Burton's Beetlejuice. A first-billed Jack Nicholson is a manic ball of energy as the Joker, against whom Batman is pitted. The hero/villain dynamic, in conjunction with Anton Furst's toweringly broody Gothic set designs, would exert an enormous influence, as would Danny Elfman's thunderous score.

Misfiring 1990s comic book movies including Dick Tracy and The Shadow owed pretty much all of their style to Batman. Burton made things even darker and more twisted in 1992's Batman Returns, but the studio then got cold feet about his vision, and downshifted into the cartoonish Batman Forever in 1995. No matter – the influence of Burton's movie is still plain to see.

3. Batman opens the comic book floodgates:

Darkman (1990)

Some 12 years before his first Spider-Man movie, director Sam Raimi made his first excursion into the realm of comic books. Fresh off the cult success of his notorious Evil Dead horror-comedies, Raimi had sought to make an adaptation of cult comic character The Shadow. However, he was unable to secure the rights, so he instead opted to craft an original character.

The end result was Darkman, in which Liam Neeson's horribly disfigured scientist seeks vengeance on those criminals who wronged him. The film's Gothic template clearly owes everything to the game-changing impact of Tim Burton's Batman – Darkman even features a score from Batman composer Danny Elfman, replete with all manner of brooding brass crescendos and off-kilter rhythms.

At the same time, the whip-pans and crash zooms of Darkman are intrinsically Raimi, hallmarks of the style he first developed on Evil Dead. It was an approach that would later mature in the Spider-Man trilogy.

Dick Tracy (1990)

Here's another Danny Elfman-scored, post-Batman comic book release that owes a considerable visual debt to Tim Burton. Directed by, and starring, Hollywood lothario Warren Beatty, the Dick Tracy movie adapts the 1931 pulp comic strip of the same name. Given Tracy's legendary pop culture status as the precursor to the likes of Batman and Superman, one might have expected a better film.

Sadly, despite the arresting visuals, the film leaves a lot to be desired. There's no denying that the onslaught of 1930s period detail and bold primary colours creates a stylised, campy universe in which to escape. However, some stiff supporting performances from the likes of Madonna, not to mention a roaring OTT one from Al Pacino as the villain, create an odd mixture that feels over and undercooked at the same time. Elfman's score, however, rocks with its chic jazz sensibility.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990)

Amazingly, until the 1999 release of The Blair Witch Project, the first Ninja Turtles movie held the record as the world's most profitable independent production. Steve Barron's adaptation of the cult 1984 comic strip grossed $202 million against a $13.5 million budget, capitalising not just on the popularity of the franchise, but also the post-Batman hunger for all things superheroes.

Barron's conception of the turtles' home city of New York clearly owes a visual debt to Tim Burton: all festering sewers and towering buildings enshrouded in shadow. But when one sees the unnerving rubber turtle suits that represent our heroes, any notion that this will hit as hard as Batman goes out of the window.

Instead, this is a cartoonish spectacle that plays very much to a younger audience. In fact, the turtles' use of ninja weapons caused such an outcry with parents in the UK that the follow-up movie, 1991's The Secret of the Ooze, was forced to make do without such weaponry.

The Shadow (1994)

"Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?" In-keeping with Dick Tracy, The Shadow takes as its basis one of the earliest comic book heroes. Long before Batman spread his wings, The Shadow (aka Lamont Cranston) was electrifying 1930s audiences via novels, comic strips and radio broadcasts. In fact, some of the radio episodes were voiced by Orson Welles, a clear sign of how highly regarded The Shadow was at the time.

Were that the film any better – whereas Batman balanced eye-grabbing set design with intriguing character development, The Shadow foregrounds the former and largely disregards the latter. Alec Baldwin plays the opium baron turned reality-manipulating superhero, who takes on New York's criminal underworld.

The film's fantastical depiction of the Prohibition era looks gorgeous, and Jerry Goldsmith's propulsive, synth-infused score is a delight, one of the best of the decade. But there's never a sense that anyone is treating the material with much conviction.

4. The genre falls into self-parody

Batman Forever (1995)

As mentioned, Tim Burton's 1992 release Batman Returns was considered too dark and twisted for a mass audience. Warner Bros, therefore, turned to director Joel Schumacher and star Val Kilmer for the new big-screen iteration of the Batman legend, and it was certainly different to what had come before.

Resplendent in kitsch set designs, bat nipples and pantomime performances, Batman Forever was consciously engineered to recapture the family market that the disturbing Batman Returns had alienated. However, opinion was sharply divided as to its merit – many bemoaned the loss of Burton's distinctive Gothic vision.

Kilmer, meanwhile, who only starred in one such film, was struggled to live up to the quiet menace of his predecessor. There were highlights, though, in the form of Jim Carrey's Riddler and Tommy Lee Jones' Two Face, two manic, mugging baddies played by actors who reportedly hated each other behind the scenes.

It was a struggle for identity that would consume the Batman character throughout the rest of the decade. Indeed, the underlying question about dark vs light was later mirrored in the 21st-century comic book movie boom, with the genre vacillating between brooding grittiness and brightly coloured fun.

The Phantom (1996)

Getting a superhero costume right on the big screen is a tricky task. How does one acknowledge the essential escapist conceit without making the character's appearance look too ridiculous? It was a challenge that seemingly passed by Billy Zane vehicle The Phantom, which rewinds the clock and takes everything back to the ridiculous days of Adam West's Batman portrayal.

This is primarily manifest in the purple suit worn by Zane's titular character – it's presented without any sense of irony, which could be a good or bad thing. On the one hand, it's a spirited throwback to classic pulp serials; on the other hand, it looks terribly tame in the wake of Batman and other blockbuster hits.

This feeling pervades the entirety of the movie: stranded between big budget slickness and low-budget tripe, The Phantom tries hard but mostly exists as a relic of an era where superhero movies were struggling for a consistent identity.

Batman & Robin (1997)

Still, if The Phantom was daft, it was nothing compared to Batman & Robin. Here was the movie that essentially put the Bat franchise on ice for eight years – an appropriate analogy given the presence of villain Mr. Freeze. As played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, the outsized, over-designed Freeze is emblematic of the movie as a whole, which tips over from engaging superhero movie into a gaudy theatrical production.

So derided was the movie, not to mention the performances, that it prompted an apology from director Joel Schumacher and star George Clooney. (The actor thought it had killed his career stone dead, before he later teamed with Steven Soderbergh on 1998's Out of Sight.) If Burton's Batman movies had got too dark, this went too far in the other direction, losing any sense of emotional engagement in the process. Fortunately, a hero would later rise in the form of Christopher Nolan...

5. Marvel first asserts itself:

Blade (1998)

Thought Black Panther was the first feature-length comic book movie with a black character at its centre? We'd like to draw your attention to the pre-Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) era of Blade, in which Wesley Snipes cuts loose and kicks ass as the titular vampire hunter, or 'day walker'.

Although a Marvel property, the first Blade movie (and its sequels) doesn't play nice when compared with its family-friendly MCU successors. The 18-rated horror-adventure has more of a feel of a strobe-laden, gory, independent movie, one complete with thumping techno music and intriguing cast, including Backbeat's Stephen Dorff as warring vampire leader Deacon Frost.

In the late 1990s, superhero movies weren't necessarily designed as puzzle pieces within a larger franchise. Although Blade did spawn two other movies, it now feels like something of a relic from the analogue era, a film allowed to stand on its own two feet as a self-contained story.

It had been a patchy decade for superhero films up to 1998, with Marvel's notorious attempts at both Captain America and Fantastic Four requiring expulsion from the mind. Other efforts, including Billy Zane vehicle The Shadow and the infamous Batman and Robin, were derided as infantile nonsense.

Thanks largely to the conviction and charisma of Snipes' portrayal, the first Blade movie set the standard for relatively serious-minded, character-driven comic book thrillers.

X-Men (2000)

Director Bryan Singer grafted serious social issues onto the comic book movie template with the first X-Men. It was a hugely successful decision, awakening audiences to the possibility that such films could be about more than just the costumes. The film's implicit social critique, combined with breakthroughs in CGI effects (spurred on by the earlier likes of Jurassic Park), invested X-Men with a degree of depth unprecedented in the genre.

This relatively high-minded approach to a story about outcast mutants with super-powers got an added boost thanks to two main players. British stage and screen veterans Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen do an excellent job selling us on the personal conflict between X-Men leader Charles Xavier/Professor X and Eric Lensherr/Magneto. The presence of two British thesps in popcorn material such as this would prove influential on the later likes of Batman Begins, which similarly sought established, sophisticated actors to sell its themes.

X-Men does an effective job of couching a story about social anxiety and body horror within an audience-friendly story involving claws, lightning powers and more besides. It spawned a franchise that continues to this day, although the real breakout success was actor Hugh Jackman as Logan/Wolverine. Then unknown, he was a late replacement for Dougray Scott – the feral charisma and inner torment of Jackman's portrayal would prove to be the highlight of the later X-Men movies, eventually reaching its emotional peak in 2017's Logan.

6. Prestige filmmakers put their own spin on the material

Unbreakable (2000)

Fresh from the success of The Sixth Sense, writer-director M. Night Shyamalan was free to do whatever he wanted. He decided to make an intensely personal, offbeat movie named Unbreakable, which reflected his long-held love of comic books.

Way before the self-referential likes of Kick-Ass, Shyamalan delivered a defining big screen commentary on the enduring power of comic book tropes, both visual and thematic. The film takes a decidedly low-key, naturalistic air to something that would be perceived as ridiculous, cleverly grounding a fantastical superhero origin story with a subdued colour palette.

Bruce Willis plays security guard David Dunn, who emerges from a horrific train crash miraculously unscathed. While he tussles with the notion that he may be invincible, David comes to realise that, as per the terms of comics, he needs an antagonist to make his journey complete. (In a sense, Shyamalan also anticipated the dynamic of The Dark Knight.)

Step forward Samuel L. Jackson's brittle-boned Elijah Price aka Mr. Glass. Jackson's performance is, like Willis', decidedly non-melodramatic, constantly forcing us to question the nature of the film's reality. At the time, Unbreakable was regarded as something of an overlooked gem. However, with the arrival of quasi-sequel Split and proper follow-up Glass, the movie can be seen for what it is: an outlier in the genre whose atmosphere and storytelling predicted much of what was to come in the following decades.

7. Comic book movies break new records:

Spider-Man (2002)

Many comic book movies had set remarkable standards of financial success, most notably Tim Burton's Batman. But it was Sam Raimi's first Spider-Man movie that reshaped what the genre was capable of in an economic sense. The global outpouring of enthusiasm for Spider-Man was so overwhelming, the film shattered records to gross more than $800 million worldwide.

The success of one Spider-Man film was therefore equivalent to two Burton Batmans. Immediately, it was clear that the comic book movie was making in-roads as its own genre, forcing a new perception of tentpole blockbuster releases.

It was increasingly clear that comic books were no longer the enclave of outcast nerds, but a credible money-making enterprise, the movie adaptations of which could comfortably sit in the midst of the peak summer season.

There are many reasons why Raimi's film soared so high. On the one hand, it capitalised on the longstanding hunger for a Spider-Man movie – unlike his Marvel brethren like X-Men and Blade, Spidey had to wait a long time for his moment in the sun. Raimi's kinetic direction (familiar from the likes of Evil Dead), combined with increasingly sophisticated CGI during the web-swinging sequences, was also nothing less than an intravenous injection of comic book nirvana. The sheer energy of the movie clearly endeared it to fans the world over.

Raimi and star Tobey Maguire would go on to make two more Spider-Man movies – of the sequels, 2004's Spider-Man 2 is arguably the finest to ever feature the character. Thanks to Raimi and Maguire's efforts, Spidey became a powerhouse, to the extent he has been rebooted twice with Andrew Garfield and Tom Holland in the title role.

8. Christopher Nolan transforms the genre:

Batman Begins (2005)

If X-Men dealt with dark themes, it was merely a dry run for Christopher Nolan's transformative Batman Begins. This sombre and engrossing comic book origin story was uncompromising in its serious take on the Batman legend – but then it had to be, given what had come before.

It's easy to forget that, prior to Nolan's reboot, the most recent movie in the franchise had been Joel Schumacher's Batman and Robin, a day-glo nightmare wrapped in gaudy sets and atrocious acting. Nolan's sense of artistic credibility and integrity wasn't just welcomed – it was needed to save Batman as a character.

The Memento and Insomnia helmer restored dignity to the Dark Knight, and also popularised the concept of the superhero origin story. Working with a mercurial Christian Bale, Nolan strips out the OTT comic book tropes to fashion a relatively plausible story about an outcast billionaire who essentially weaponises fear to fight his enemies.

This psychological imperative is not only present in the performances, but the aesthetic of the movie. Gone is the fairy tale approach of Tim Burton; in comes a far more utilitarian approach that distills the feel of crime master Michael Mann. (The filmmaker's Heat would be a profound influence on the later The Dark Knight.)

Somewhat unfortunately, 'dark and gritty' became a cliched approach in the years following Nolan's groundbreaking movie. Filmmakers aped the look but struggled to grasp the dramatic intuition, which is resplendent in an excellent cast of veterans including Liam Neeson, Gary Oldman, Morgan Freeman and Michael Caine.

9. The Marvel Cinematic Universe is born:

Iron Man (2008)

Looking back, Iron Man was hardly expected to work as a standalone movie, let alone give birth to the biggest comic book movie franchise of all time.

A superhero adventure based on a second-tier Marvel character that many people hadn't heard of, starring an actor whose best days appeared to be behind him. The odds were so solidly stacked against Iron Man that its eventual success was all the more profound. And, of course, the main reason for said success was the delightful synergy between character and star.

Robert Downey Jr.'s performance as Tony Stark not only revived his career; it also secured his place at the heart of the ensuing Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Directed by Jon Favreau, Iron Man established so many of the tropes that we've come to take for granted in comic book cinema, including the post-credits scenes that have us salivating for the next instalment in the franchise.

Deeper than that, however, Iron Man restored a sense of lighthearted fun to a genre that had become increasingly bogged down in gloom and misery. This lightness of touch was to become the MCU's calling card, with even the most serious of situations punctuated by a lighthearted joke. The careful balance of dramatic investment and jokey fun gave rise to a phased series of comic book blockbusters, and the fourth of those stages is set to kick off with Black Widow.

Iron Man achieved the impossible: it restored credibility to its star, and also made studios realise the lucrative potential of secondary comic book characters, Marvel and otherwise. The serialised storytelling, whereby one character's arc would be continued in both standalone movies and ensemble blockbusters, revolutionised the comic book genre, and forever changed our viewing habits.

10. The comic book movie becomes more than just a comic book movie:

The Dark Knight (2008)

Searing in tone and ambitious in conception, The Dark Knight emerged in summer 2008 to blow apart any simplistic notion of the comic book blockbuster. In truth, this brooding story of a city teetering on the edge of chaos is less a superhero movie than a thrillingly mounted crime drama with a superhero at the centre of it.

In the wake of Batman Begins, critics further applauded Christopher Nolan's grounded sense of emotion. Even though The Dark Knight embraces a legacy of DC comic book storytelling, most notably the likes of Frank Miller, every aspect of the film is engineered towards plausibility. As with Batman Begins, this is writ large in everything from the production design to the cast, but the dark, tortured heart of the movie is located in the Batman/Joker relationship.

Whereas earlier Batman films had treated this antagonistic yin/yang rivalry as something of a pantomime, Nolan and sibling co-writer Jonathan refashioned the struggle as something far more terrifying. As envisaged by the late Heath Ledger (on sensational, Oscar-winning form), the Joker is to all intents and purposes a 21st-century terrorist whose role is to steadily pick apart the stitches in the fabric of our society.

He steadily awakens Christian Bale's Batman to this appalling revelation, in the process making the title character realise that good and evil aren't so easily disassociated from one another. The startling psychological impulses and emotionally mature grace notes were unheard of for a film in this genre. Nolan had arguably taken it to the next level, securing The Dark Knight not just as a commercial blockbuster but an artistic prestige picture filled with thought-provoking moments.

Watchmen (2009)

Alan Moore's pioneering graphic novel may deal in fantastical characters and conceits, but at its heart, the story is a jet-black, politically charged story of identity and destruction. Watchmen has recently been revived by Lost and Prometheus writer Damon Lindelof for HBO, but it was 300 director Zack Snyder who first tackled Moore's multi-layered masterpiece.

Opinions remain split as to Snyder's take: many admire the ambition and full-blooded nastiness not often seen in a movie of this type. Fans also applauded the filmmaker's loyalty to the visual approach laid down in the graphic novel. For many others, however, Watchmen is an overly simplistic distillation of a deeply complicated source, more concerned with the lycra costumes of the cast than the underlying meaning.

Nevertheless, there's no denying that Watchmen stands out from the comic book crowd as a dark, tortured beast, one that is decidedly not for the kiddies. Moore may have distanced himself from the project, saying in advance of production that he put a curse on it, but Watchmen proved that comic book films were continuing to evolve in intriguing ways.

Kick-Ass (2010)

Kick-Ass is a somewhat rare beast in the comic book realm: an independently financed project that is subsequently free to go as crazy as it wishes. Liberated from the constraints of studio interference, director Matthew Vaughn and screenwriter Jane Goldman, working from Marc Millar's graphic novel, can gleefully blow the whole genre apart.

The word 'meta' barely describes the irreverent tone of Kick-Ass. The entire movie works on two levels, both as a deconstruction of superhero origin cliches and a celebration of them. The film revels in ironies, beginning with Aaron Taylor-Johnson's central character Dave. He has no superpowers, but aspires to become a hero, named Kick-Ass, in order to save his city.

He's eventually joined by Mindy aka Hit-Girl (Chloe Grace Moretz) who, in the film's most memorably controversial, Daily Mail-baiting move, is a young girl with a sweary vocabulary and a penchant for knives. Throughout, the movie embraces a sense of violent anarchy and dark humour that makes it genuinely hard to predict where the story is going.

By the time Kick-Ass arrived, the comic book genre was well-established enough on the big screen that jokes could be made at its expense. At a time when Marvel and DC were increasingly asserting their stranglehold, jaded viewers were starting to think they'd seen it all. But Kick-Ass punched new life into the format, taking comic book movies fully meta for the first time in history.

Scott Pilgrim vs the World (2010)

Hot on the heels of Kick-Ass, the deliriously entertaining Scott Pilgrim demonstrated just how much self-referential humour could be mined from the comic book template. Directed by Shaun of the Dead's Edgar Wright, the film's tone is more affectionate and audience-friendly than its predecessor, although even more dizzying and overwhelming with the sheer amount of gags it throws out.

Michael Cera plays the eponymous Scott Pilgrim, a likeable slacker who must battle his new girlfriend's seven evil ex-boyfriends in battle. Fittingly enough for a filmmaker so immersed in pop culture, Wright ensures that every frame of the movie is loaded with visual references and jokes, both overt and covert. Take the appearance of Chris Evans' vain movie star for instance, who cracks his neck to the sound of Jerry Goldsmith's Universal Studios fanfare.

The whole visual tapestry of the movie fizzes and pops with the authentic feel of a comic book panel. From the over-exaggerated punches to the emergence of eye-popping superpowers, the film literalises the physics-busting nature of our favourite comic books. It is, by turns, euphoric, silly, and, ultimately, very sweet.

11. Marvel becomes a powerhouse:

Avengers Assemble (2012)

Come 2012, Marvel Studios had established sufficient confidence in their solo superhero movies, namely Iron Man, Thor and Captain America. All had proven critical and commercial successes, but the real test was yet to come: how would all these outsized comic book personalities gel in a single movie? After all, containing and harnessing Robert Downey Jr.'s Tony Stark would be a huge challenge all on its own.

In the end, Buffy creator Joss Whedon emerged as the hero of the hour, achieving what many thought impossible. In assembling the Avengers on the big screen for the first time, filmmaker Whedon gave just enough balance to each individual character's arc, while also fashioning brilliantly antagonistic, chippy chemistry in the ensemble scenes. It was a technique that the later likes of Justice League, a DC property, found deceptively hard to manage. (Ironically, that was also helmed by Whedon after Zack Snyder pulled out.)

The end result was nothing less than sheer comic book nirvana, signalling that Marvel was really onto something. The record-breaking success of Avengers Assemble (at $1.1 billion, their biggest hit to date) empowered the studio to further expanded the concept of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Thanks to Whedon's efforts, a road map was laid out involving further team-up movies (the director would return for 2015's Avengers: Age of Ultron), additional solo films, and brand new movies involving characters we hadn't met yet. It was a strategy aped by other studios, including DC with their own Extended Universe, but few attained this level of success this early on.

Guardians of the Galaxy (2014)

Many individual films within the MCU have been infused with the personality of their directors. But Guardians of the Galaxy really was something else: an idiosyncratic, pop-infused kaleidoscope of a journey through the farthest reaches of space. Arriving six years into the lifespan of the MCU, the first Guardians movie made it apparent that even within a franchise template, there was scope for genuine, joyous eccentricity.

Directed by James Gunn, Guardians of the Galaxy assembles the most unlikely ensemble in the MCU, and makes a virtue of their sheer weirdness. The team is led by a brilliantly charismatic Chris Pratt as the rogueish Peter Quill/Star Lord, and encompasses Zoe Saldana's green-skinned Gamora, the Bradley Cooper-voiced Rocket Racoon, the Vin-Diesel voice tree-like Groot and Dave Bautista's bruising Drax the Destroyer.

It's a set-up with every potential for disaster, yet we can recognise aspects of our own flawed personalities in these delightfully outlandish characters. Essentially, the team becomes something of a family, which creates human appeal in the midst of eye-widening CGI set-pieces. The cherry on the cake is the sublime soundtrack, beginning with that wonderful Redbone number 'Come Get Your Love' during the opening sequence. The juxtaposition of a comic book universe with rocking hits from the likes of David Bowie was a brilliant move, copied to increasingly lesser degrees in the later likes of Suicide Squad.

12. The comic book movie is further turned inside out:

Deadpool (2016)

What comic book hero has the sheer nerve to call out his director as 'An Overpaid Tool' during the opening credits? Deadpool, that's who. The meta nature of Ryan Reynolds' fourth-wall-breaking ball of energy makes Kick-Ass look contained and subdued by comparison. Mr. Pool even invades his own flashback sequences, in the process leading to a "sixteen-wall" collapse.

Punky, anarchic, violent and very funny, the first Deadpool movie has more of a feel of an improvised comedy than a traditional superhero movie. Even the constituent elements are ruthlessly mocked: the presence of two X-Men side characters is attributed to the fact that the main team were too expensive to afford. No Marvel character has broken so many rules in terms of his tone or approach.

However, that's precisely what made Deadpool resonate with audiences. The movie was positioned as a Valentine's Day 2016 release, and thanks to a canny marketing strategy pitching it as an anti-romantic offering, audiences lapped it up. The film went on to gross more than $700 million worldwide, and spawned a hit sequel in 2018. Deadpool's success also awakened the potential of a regular February release slot for superhero movies, later replicated by Logan and Black Panther.

Logan (2017)

When is a comic book movie not a comic book movie? Answer, when it's actually a Western in disguise. Some 17 years after he first took on the role of Wolverine, Hugh Jackman finally got the material he deserved in this despairing yet compassionate thriller, one that finds the titular superhero in the twilight years of his life.

Much like The Dark Knight before it, Logan broke new ground with its mature depiction of a longstanding comic book icon. The film strips away the OTT excesses of its X-Men predecessors while ramping up the savage levels of violence, fully immersing us in a world where mutants have been all but obliterated. Like Nolan's movie, Logan finds human impulses and emotions within a fantastical scenario. This primarily manifests in the moving relationship between Logan and his ailing mentor, Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart), an Alzheimer's sufferer who is wracked with deadly seizures.

The film openly acknowledges the influence of classic Western Shane ("there's no living with a killing"), refashioning Logan as a tortured outlaw on a blood-soaked, cross-country odyssey. By removing most of the familiar X-Men iconography (Logan himself dismisses a comic book representation of how mutant-kind was decimated), director James Mangold is able to make the most emotionally resonant movie in the series. Logan is a marking point in the wider comic book genre, a sign of how movies within certain franchises can strike specific, striking tones.

13. A DC icon gets her dues:

Wonder Woman (2017)

Forget the whole spinning in a circle schtick of Lynda Carter; DC's big-budget Wonder Woman movie reclaimed the character from her campy TV origins, in the process helping to balance out the traditionally male-heavy comic book genre.

Key to the film's impact is the memorable central performance from Gal Gadot. She's convincing both as the badass Themysciran warrior and also the bumbling, fish-out-of-water figure in the midst of World War I. Gadot's facility with both action and light comedy helps the movie of Wonder Woman to work as both a dramatically engaging origin story and a none-too-serious bit of escapist fantasy.

The movie is directed with great panache by Patty Jenkins, who had earlier bailed on Marvel's Thor: The Dark World. Jenkins made history by becoming the first woman director to helm a movie in the genre, and the impact of that decision is currently rippling through the industry. Thanks to Jenkins' pioneering presence, we'll soon get the likes of Black Widow from Cate Shortland and The Eternals from Chloe Zhao. It took a long time for the genre to reach this point, but thankfully it now has.

14. The world assembles for the Avengers:

Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

Not merely a collection of individual superhero stories, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) has steadily taken on the quality of a long-form narrative. Important plot elements and characters have been seeded at strategic points during the MCU's development, later flowering and taking on greater significance.

Throughout the course of the MCU, it's also become clear that these beloved Marvel characters will have only a finite lifespan, conditional on an actor's contract. The question of how and when the likes of Tony Stark and Steve Rogers would eventually depart the MCU reached fever-pitch in the colossal Avengers: Infinity War.

In this movie, the scale of the threat facing the Avengers couldn't be deflected with a shrug or a quip. The diabolical Thanos (Josh Brolin) had first been teased during the post-credits scene of Avengers Assemble, and he now emerged as the deadliest-ever MCU villain, one capable of obliterating half of all life in the universe.

By this stage, the world was so invested in the MCU that it turned out en masse to witness the devastating impact on the Avengers collective. The Russo brothers' appreciably dark conclusion to Infinity War demonstrated that there are real emotional stakes in this franchise, a sign of how much the MCU has matured over the years. Little wonder that the movie grossed an ear-splitting $2.048 billion worldwide – these were no longer movies but monumental global events.

Avengers: Endgame (2019)

Avengers: Infinity War was just one half of an epic story designed to devastate our emotions. When Thanos achieved his universe-obliterating snap, it was natural to speculate on how the Avengers would bounce back.

The answers had, of course, been planted elsewhere in the MCU, a sign of the franchise's careful road map and plotting strategy. The interlinking relationship between the various Marvel films paid off in Endgame, which was no mere movie but the gargantuan payoff to 12 years worth of storytelling. A blockbuster of such magnitude only tends to arise once in a generation, and this pivotal moment in the MCU subsequently toppled Avatar to become the highest-grossing film of all time.

It was a moment of sublime euphoria for comic book fans, who had stayed loyal to the franchise's arc from the relatively humble Iron Man to the world-conquering success of Endgame. Contained within that journey is a heartening message about how comic book movies have increasingly become embraced as the de facto blockbusters of the 21st century. Accusations of nerdery and cheesiness are no longer acceptable – these movies now have the capacity to transcend barriers between comic fans and non-comic fans alike.

It's perhaps best embodied in the climactic funeral sequence, as we bid farewell to Robert Downey Jr.'s Tony Stark. As the godfather of the MCU takes his bow, we come to perceive the impact that a single comic book character can have on the global moviegoing community. If that's not a sign of how much comic book movies have progressed in the last 10 years, then nothing is.

15. Comic book movies become artistic successes:

Black Panther (2018)

As the first-ever African superhero in comic book lore, Black Panther (aka T'Challa) made his debut in 1966. Creator Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby broke down social norms with a black saviour figure whose nation of Wakanda harbours extraordinary levels of resource, in the process deflecting crude stereotypes and advancing the comic book format further.

It would take 52 years for T'Challa to make his solo movie debut in Black Panther. (He had appeared earlier as part of the MCU ensemble in Captain America: Civil War.) The film was forced to shoulder an enormous amount of expectation, not least because the title character carried so much cultural and emotional importance for black communities the world over.

That Black Panther emerged as a thrilling success was a cause for both relief and celebration. Like Blade before it, the film awoke Hollywood studios to the notion of black characters leading their own blockbuster properties.

Directed with verve by Ryan Coogler, the movie is anchored by a sturdy Chadwick Boseman in the title role, although, like the earlier The Dark Knight, the show is stolen by the villain. Michael B. Jordan's insurgent Eric Kilmonger is one of those informed, seductive antagonists whose own crusade challenges the isolationist philosophy of Wakanda, in the process exposing doubts in our hero. These engrossing emotional undercurrents sit alongside the expected CGI-heavy set-pieces to fashion one of the most entertaining Marvel movies.

Not just a blockbuster success, Black Panther was also a significant artistic one. It was the first superhero movie to be nominated for Best Picture, and the first Marvel movie to win any kind of Oscar. It received the genre's first-ever Oscar for Best Original Score (for Ludwig Goransson), and costume designer Ruth Carter became the first-ever African-American woman to land the trophy. Meanwhile, production designer Hannah Beachler became the first-ever woman of colour to be nominated in her respective category, a nomination she eventually converted into a win.

Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018)

If Black Panther was the first superhero movie to be nominated for Best Picture, then Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse advanced the genre further. This imaginatively designed animation was the first comic book movie to win any kind of best film award – in this case, the highly coveted Best Animated Feature. No mean feat when the competition that year included Incredibles 2 and Isle of Dogs.

Conceived and produced by LEGO Movie gurus Phil Lord and Chris Miller, Spider-Verse has staked its claim to being possibly the best Spider-Man movie of all time. There are many reasons for this, and they go beyond the breathtaking visual aesthetic.

In large part, the film's success is down to the expansion of the Spidey universe: three live-action reboots down the line, this movie manages to achieve something truly unique. It actively has multiple Spidey characters occupying the same space, allowing for equal parts pathos and off-the-wall humour. It also deepens our understanding of the Spider-Man legend, reminding us that the baton can be passed from the overly-familiar Peter Parker to other equally endearing outcasts. Given our general exposure to Spider-Man on the big screen, it's remarkable that this film is aglow with the thrill of rediscovery.

Joker (2019)

More than four decades after Superman's release, comic book movies finally achieved a platform at international film festivals. Directed by Todd Phillips, Joker channels the grubby spirit of Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver to give the Clown Prince of Crime a decidedly plausible origin story.

The film's level of conviction is primarily driven by star Joaquin Phoenix. He's typically ferocious and uncomfortable as struggling clown Arthur Fleck, whose litany of personal humiliations causes him to morph into a symbol for the oppressed masses of Gotham City. There's relatively little that's fantastical about the movie, and certainly nothing that occupies clear-cut good vs evil morality. In this iteration of Gotham, everyone is feeding off one another.

The film first stoked attention at the Venice Film Festival, where its surprise appearance was compounded by a revelatory Golden Lion win – it was the first superhero movie to achieve such success. As controversy raged about the film's depiction of violence, it soared to enormous box office success, and eventually converted all the attention into a Best Actor Oscar win for Phoenix. It was the first film in the genre to win in the category – an encapsulation of how far comic book movies had come since Christopher Reeve first convinced us a man could fly.

What's your favourite comic book movie of all time? Let us know @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.png)