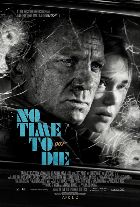

The 25th James Bond movie No Time To Die arrives in Cineworld in September, and we're counting down the days by revisiting all the 007 movies in chronological order of release.

In honour of Daniel Craig's swansong as 007, we're taking a nostalgic trip back through time. Today's film: Moonraker, starring Roger Moore...

What is the story of Moonraker?

Space shuttle Moonraker has disappeared without a trace, and British agent James Bond/007 (Roger Moore) is sent to investigate. Suspicion naturally falls on Moonraker designer Hugo Drax (Michael Lonsdale), and after several attempts on Bond's life, it's clear the enigmatic industrialist has something to hide.

Bond's journey takes him from California to Venice to the outer reaches of the Amazon rainforest, as the diabolical Drax's plan becomes clear: he aims to obliterate life on Earth and build a new human colony from his space station operating in our orbit. Fortunately, Bond has help in the form of CIA agent Holly Goodhead (Lois Chiles).

How did Moonraker get made?

Released in 1977, The Spy Who Loved Me was a tremendous critical and commercial success for Roger Moore's 007. The franchise had been under threat of going out of date with the lambasted The Man with the Golden Gun. Yet Spy's mixture of globe-trotting locations, humour and lavish production values (propelled by the newly built 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios) helped rekindle nostalgic memories of the franchise's golden era in the 1960s.

Spy's success was all the more impressive given it was released in the summer of the first Star Wars movie. George Lucas's space opera would swiftly ascend to become the most financially successful movie of all time. And although there was never a chance Bond could compete with such extraordinary box office grosses (upwards of $700 million), it was heartening that audiences were still willing to engage with the world of 007.

Of course, the astronomical box office of Star Wars was bound to have an effect in one form or another. When it came to making Spy's follow-up, Moonraker, it was inevitable that Bond would be influenced by Lucas's record-breaking creation; this mirrored the wider shifts going in the franchise during the 1970s. Actor Roger Moore's debut as 007, Live and Let Die, was a clear response to blaxploitation cinema, while the aforementioned Golden Gun attempted, unsuccessfully, to assimilate the tropes of kung fu movies.

The Bond franchise was no longer setting trends; it was mirroring them. Therefore, in the wake of Star Wars, Bond would make his first (and so far only) journey to space in Moonraker, one of the most self-consciously ridiculous movies in the franchise. It was a far cry from the relatively plausible shenanigans of Spy, whose action had remained resolutely Earthbound. That Moonraker remains, at the very least, watchable is almost entirely down to Moore, whose assured comic delivery and perfectly timed raised eyebrow make it clear he's as much in on the joke as the audience is.

As a clear indication of the impact of Star Wars, Moonraker took the place of the proposed For Your Eyes Only. The latter would instead be released in 1981 as Moore's fifth Bond movie. In fact, Bond author Ian Fleming had first conceived Moonraker as a movie, before transforming it into a novel, first published in 1955. However, the film adaptation, in keeping with many of the Bond films, ditched many aspects of Fleming's construction to become its own ridiculous entity, where a perfectly timed quip is as deadly as a precision-aimed space laser.

Certain aspects of the novel remained, including the presence of villainous industrialist Hugo Drax, played in the movie with enjoyably detached delivery by French actor Michael Lonsdale. The film also retained Drax's attempt to roast Bond and his companion (Holly Goodhead in the film) beneath the rocket of a space shuttle. Otherwise, screenwriter Christopher Wood's adaptation was so far removed from Fleming's source material that Wood was commissioned to write a tie-in novel, named James Bond and Moonraker, published in 1979 to tie in with the film's release.

Wood had contributed a measure of structure and emotional believability to Spy, although few of those qualities are present in Moonraker. Truly, Moore's portrayal of 007 is a somewhat impervious superhero, where even the most dangerous of situations (being G-forced to death in a centrifuge simulator) leads, at best, to a temporary sense of peril. Rest assured, in the next scene, he's back to his smirking, flippant self.

And yet, tonally, Moonraker is blighted with the same issues that affected The Man With The Golden Gun. It haphazardly veers between cartoonishness and surprising moments of brutality, not least in the haunting execution of Drax's employee Corinne (Corinne Clery). Upon discovering she has granted Bond access to top-secret documents, Drax sets his dogs on her, putting in motion an eerie chase through sun-dappled woodlands set to John Barry's tragedy-laden score.

It's one of the most upsetting moments in a Bond movie, and sits uneasily alongside the more knockabout moments. This includes the decision to give Jaws a new girlfriend, Dolly, played by Blanche Ravalec, which completely neuters the sense of threat the character posed in The Spy Who Loved Me. The filmmakers were initially unsure of the discrepancy in height between Kiel and the relatively diminutive Ravalec, before Kiel revealed that his actual wife was the same height. It would be Kiel's final appearance in a Bond movie.

Poignantly, Moonraker was also the last appearance from Bernard Lee as M. The veteran British actor had played Bond's superior since the inception of the franchise, and brought a memorably taciturn authority to the role. It's perhaps a shame that his final 007 scene is the infamous 're-entry' climax where Bond is caught in flagrante in zero gravity with Goodhead.

On that note, if we're talking Bond women with outrageously suggestive names, then they don't come more so than Holly Goodhead herself. It's therefore a shame that Lois Chiles' performance is so wooden that we don't invest in the chemistry between her and Moore. Maybe it would have been better for the ill-fated Corinne Clery to be Bond's ally? Even so, Chiles (who had earlier turned down the role of Anya Amasova in The Spy Who Loved Me) still gets things to do; spare a thought for poor Lois Maxwell as Moneypenny, sidelined yet again as she was throughout so much of the Moore period.

For all its weaknesses, Moonraker does boast some truly impressive stunt work and location photography. The set-pieces kick off in fine style with a pre-credits skydiving scene, as Bond attempts to wrestle a parachute from a treacherous pilot in mid-air. Shot above Lake Berryessa in California, the stunt was supervised by second unit director John Glen, who would make his debut as a Bond helmer with For Your Eyes Only.

In total, 86 skydives were undertaken by the team over several weeks, including stuntman Jake Lombard, who portrayed Bond during the hair-raising sequence. Specially designed parachutes were made to be concealed beneath the costumes of the stunt team; said clothing would then tear during the final moments when the 'chutes would open. A special lightweight, anamorphic, Panavision camera lens was attached to the helmet of the skydiving cinematographer to capture the achievement in all its glory.

Shot on a budget of $34 million, making it one of the most expensive Bond movies so far, Moonraker has a suitably expansive range of locations under its belt. From the canals of Venice to the the palatial splendour of Drax's palace (said to be California; in fact, it was the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte outside Paris), to the humid greenery and awe of Iguazu Falls in Brazil, Moonraker flaunts its production values, and then some. Bond enjoys some samba in Rio de Janeiro (although Moore's arrival on set was delayed owing to kidney stones), and tussels with Jaws on a paralysed cable car, filmed on the city's Sugarloaf Mountain. Another perilous stunt, this almost led to the death of stuntman Richard Graydon. (For the moment where Jaws bites into a steel cable, the prop was made of liquorice.)

The film was also another opportunity for production designer Ken Adam to reveal his majestic creations. The veteran Bond crew member had been responsible for Blofeld's volcano base in You Only Live Twice, and the interior of the submarine-devouring Liparus tanker in The Spy Who Loved Me. Given Moonraker takes place in the uncharted regions of space, Adam's imagination could go wild when envisaging Drax's space station, where he plans to breed a new colony of human beings while life on Earth perishes. (One of the chosen people was played by Lois Maxwell's daughter, Melinda.)

Interestingly, the interior photography was temporarily uprooted from the traditional Pinewood Studios in the UK to France; this was because of high taxation in the UK at the time. Adam required 222,000 man hours to construct his elaborate sets, which were captured at the Epinay and Boulogne-Billancourt Studios in Paris. The aforementioned space station set continues to hold the record for the most zero-gravity wires used in a scene.

It was all suitably indicative of an expensive, outlandish Bond film that had spectacle to spare – but was this to determine the future of the franchise?

READ MORE

- No Time To Die and the 6 James Bond movies we never got to see

- 7 actors who could play James Bond after Daniel Craig retires

- Shaken and stirred! Daniel Craig's defining 007 moments

What music is on the soundtrack for Moonraker?

Cutting through the cartoonish noise and nonsense of Moonraker is John Barry's typically elegant score. Oddly enough, given the camp, buffoonish tone of the movie, it inspired Barry to craft one of his lushest, most beautiful Bond scores. One can possibly sense Barry's dismay at how much the Bond franchise was sinking into self-parody, and how determined he was to showcase his formidable capacity for sweeping melody, regardless of how much this runs counter to the farcical nature of the action sequences.

It all begins with the title song, performed, in her third and final Bond venture, by Shirley Bassey. Reportedly, the singer didn't think much of the end result, having had little time to prepare, but there's no denying that her tremulous voice, Hal David's evocative lyrics and Barry's supple underscore make for a classic Bond theme. (That said, the disco rendition over the end credits has dated badly.) The string-led melody of the song underpins the remainder of Barry's score - he really was a master at threading together the emotion of the credits sequence with the remainder of the narrative.

Barry's score was recorded in Paris, as opposed to the UK, for tax reasons. Maybe this is what helped infuse the Moonraker score with an added sense of romance and magic. The gorgeous, string-lined statements of the main song theme are very much in line with Barry's romantic 1970s idiom, familiar from the acclaimed likes of Walkabout and The Last Valley. This style would come to dominate Barry's 1980s output, including the celebrated, Oscar-winning Out of Africa in 1985.

Somewhat unusually for a Bond score, Moonraker deploys a choir for added wonderment. This is notably apparent in 'Bond Lured to Pyramid', in which the fluttering woodwinds and alluring vocals almost serve as a siren's call, luring 007 to his encounter with a deadly python in Drax's hidden temple.

The choir combines with a subtle samba influence for 'Bond Arrives In Rio', a wonderful example of Barry's ability to transition to different environments and countries. This is then followed by a stately reprise of the '007 Theme' in 'Boat Chase' – this secondary Bond piece had appeared on and off throughout the franchise, and to date this is its last appearance. The way in which Barry replaces the theme's rambunctiousness with a far more elegiac tone is another example of his brilliance in adapting his own Bond material.

Despite this, the main Bond theme is only deployed on the odd occasion. Its most prominent appearance is during the opening skydive sequence, acting as a suitable reflection of Bond's heroism and resourcefulness. The track also features during the ridiculous Venice canal pursuit, in which Bond breaks out a gondola with a propeller and an ability to travel on land – to the astonishment of a double-taking pigeon.

The score's apex occurs in 'Flight Into Space', which attains a level of awe and nobility rare in a Bond soundtrack. The nature of the sequence allows Barry's music to take centre stage and he doesn't disappoint, building clusters of snare drums and ominous brass (representing the omniscient Drax's hidden base) with surging strings and the ever-present choir. The piece is one of the most impressive in Barry's illustrious career, helping us to forget the silly nature of the storyline, if only for a few minutes, and engulfing us in heavenly beauty.

Strangely enough, as with the score for The Spy Who Loved Me, the soundtrack contains several musical in-jokes. The first is a statement of John Williams' theme from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, heard as a scientist taps into a keypad. Producer Albert R. 'Cubby' Broccoli had to secure director Steven Spielberg's permission to use the piece; in 1985, Broccoli responded in kind by allowing Spielberg to use the Bond theme in The Goonies.

Later on in the movie, Bond is seen decked out in traditional Brazilian dress and riding a mule to the sound of Elmer Bernstein's unmistakeable theme from The Magnificent Seven. (The track starts at 7:15 into the clip below.) It seems not even the music of the Bond movies was immune to self-parody.

How was Moonraker received?

Released in 1979, Moonraker became the highest-grossing Bond film to date, bringing in $210 million worldwide. The movie would hold this record until the release of 1995's Goldeneye, which stormed the box office with $356 million.

However, while audiences were queuing up, clearly hungry for more space-based action in the wake of Star Wars, critics were less than impressed. In fact, even key members of the crew criticised the movie; screenwriter Richard Maibum cited the movie's sillyness and stated that Moore "spoofed too much".

Entertainment Weekly described Moonraker as "the campiest of all the Bond movies". Critic Nicholas Sylvain spoke of the movie's "sheer idiocy" and Roger Ebert said the movie was far too "jammed with faraway places and science fiction".

Critical antipathy was perhaps fuelled by the contrast with the earlier The Spy Who Loved Me. That had been a relatively down to earth story by Roger Moore's standards, and had scored critical and commercial gold in the process. To many, it was inexplicable why Bond should have been propelled to such heights of silliness. Little wonder 007 was brought firmly back down to Earth in his next adventure.

What was the next movie in the James Bond series?

For Your Eyes Only was the next Bond movie, released in 1981.

When is No Time To Die released in the UK?

No Time To Die is released on 30th September. Don't forget to tweet us your favourite James Bond movies @Cineworld.

.jpg)

.png)